The Most Forgotten Core Muscle: The Diaphragm

Over the past month, I’ve worked with several clients with chronic low back pain, perpetuating anxiety, and hypertonic upper traps- all of which could be addressed by properly utilizing and exercising the diaphragm. As newborns, we are all perfect little belly breathers. Somewhere along our preordained path towards sedentary lifestyles, we begin relying on secondary muscles for breathing such as the intercostal muscles between the ribs and those in the neck and upper trapezius. Sitting for long hours with poor posture can render the diaphragm ineffective in performing its intended function, causing it to go dormant. As a result, the person becomes a “chest breather”, causing dysfunctions or tension in the head, neck, jaw, and upper back.

"The diaphragm is the powerhouse of respiration"

↓ Stress

↑ Core Strength

The diaphragm is the powerhouse of respiration, and if respiration is necessary for life, then the diaphragm is life. Despite its extreme physiological relevance in multiple systems in the body, the diaphragm continues to be underappreciated, especially in the realm of highly palatable fitness media. It makes sense; in the landscape of our “core” muscles- the diaphragm is hidden- which means the beach can’t showcase your diligence like the rectus abdominis (6-pack abs) can.

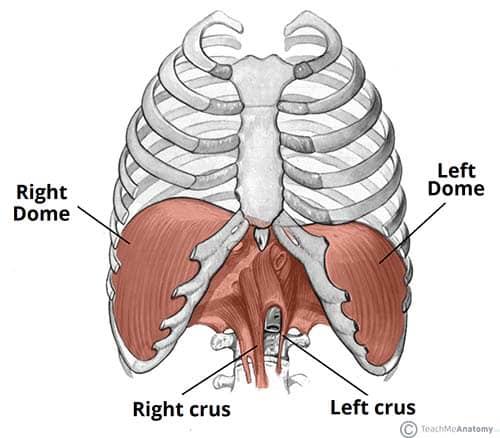

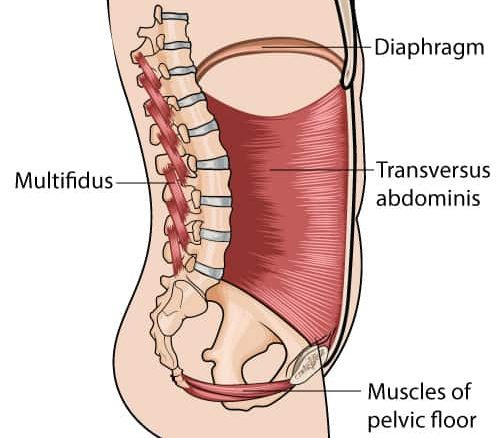

Let's start with anatomy

The Pressure Regulator

Anatomy jargon aside, let’s delve into how the diaphragm can help you reduce stress, alleviate low back pain, and strengthen your core. As a pressure regulator, the diaphragm has the ability to manipulate the position of your ribcage and pelvis for force acceptance, while influencing hemodynamics- the movement of blood- to regulate stress. There are two ways to engage your diaphragm: deep breathing and power breathing.

Deep Breathing

As mentioned earlier, we’ve evolved into sedentary creatures who rely on chest breathing. These quick, shallow breaths physiologically induce a “flight or fight” response, whether or not you feel psychologically stressed. This response constricts blood vessels throughout your body, leading to an increase in heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and digestive dysfunctions. The antidote? Deep breathing.

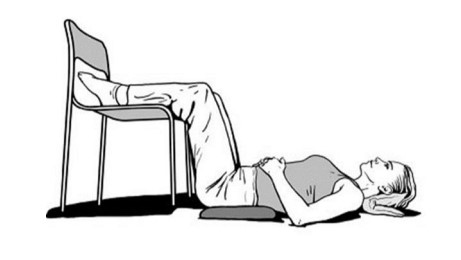

To get started, lie on your back with your feet propped up on a chair or anything that keeps your thighs perpendicular to the floor and shins parallel to the floor. This is called the 90-90 position. Place your hands on your lower ribs, and begin by fully exhaling through your mouth. Hold at the bottom for 2-3 seconds. Using this as our starting position, slowly inhale through your nose. Allow your belly to rise, and expand your ribcage through the front, sides, and back (360 degrees).

Note: Instead of aiming for maximal air, inhale until it doesn’t feel easy to bring in more air. Let the breath do the work.

Power Breathing

Now you have deep breathing in your arsenal of self-soothing techniques, let’s explore how to use our diaphragm to enhance force output and stabilize the spine. Forced expiration against a closed glottis increases intra-abdominal pressure, and provides maximal rigidity in your torso. This is also known as the Valsalva maneuver (VM) or “bracing your core”. And you’re more familiar with this maneuver than you think- it’s what you do when you cough, sneeze, gag, or defecate. To illustrate this pressure regulation system, Mary Massery’s “Soda-Pop Can Model” is a helpful analogy. The model suggests that if a soda can represents your core, regulating its pressure dictates its stability. This technique isn’t limited to weightlifting or martial arts, but its usage can mean the difference between collapsing under a heavy barbell squat or withstanding a liver shot. If you’re interested, a link to Mary Massery’s research is provided below.

One method I use to teach the VM is by incorporating familiar movements. Let’s start with a cough. Begin by coughing a few times, and take note of how it feels to brace your core. After that, keep your mouth closed and prevent any air from escaping. If you sense that you can absorb a hit to the abdomen in this position, then you’re doing it right! If not, try method #2. Pinch your nose as if you’re about to equalize the pressure in your ears- then, instead of exhaling through your nose, breathe out as you usually would with your mouth shut.

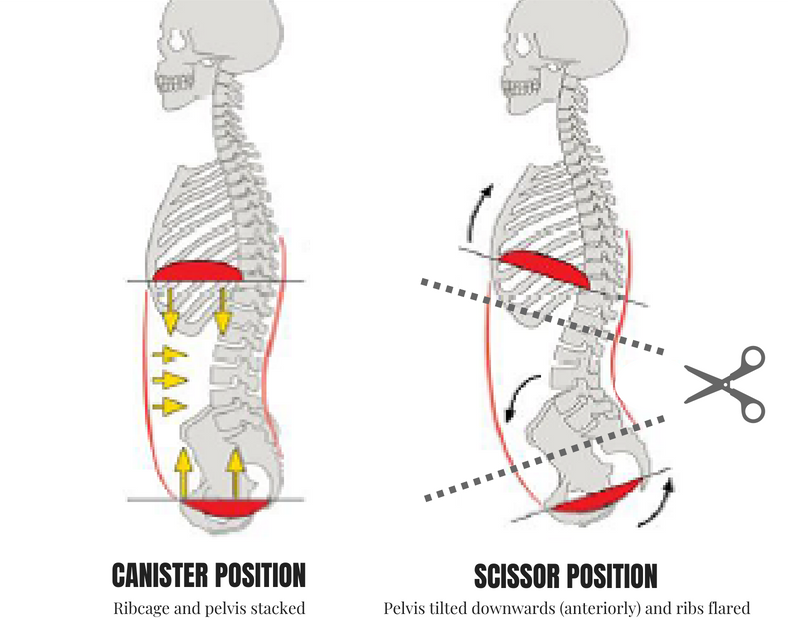

To maximize the benefits of, and utilize the VM effectively, it’s crucial to establish what’s known as the “Canister Position”. This involves stacking the ribcage directly on top of the pelvis, which facilitates coordination between the diaphragm, abdominal cavity, and pelvic floor. As a result, this position enables greater mobility by promoting independent movement of the spine and hips, while also reducing pressure on the lower back. In practice, you can get into this position by tucking in your pelvis or squeezing your glutes.

By incorporating targeted breathing exercises into your daily practice and training, you can unlock greater movement quality, leading to increased exercise capacity, improved force output, and enhanced tissue resilience. At Diep Therapy, we use myofascial release – a gentle yet effective form of manual therapy – to release diaphragmatic tension. The benefits of this approach are reflected in our clients’ reduced hip flexor tightness, as the iliopsoas shares an intimate relationship with the diaphragm. Paired with guided diaphragmatic breathing, we can help retrain your breathing mechanics, reducing chronic stress on your body.

Schedule an appointment with our RMTs at Diep Therapy today by calling (778) 901 7373!

Related Articles

Copyright © 2023 Diep Therapy